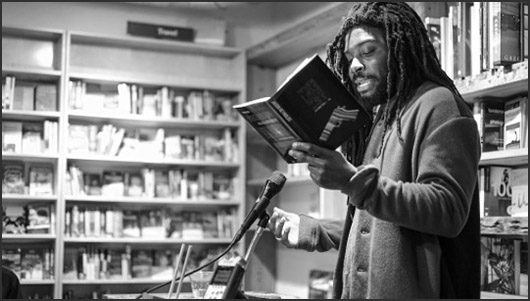

Author, Jason Reynolds

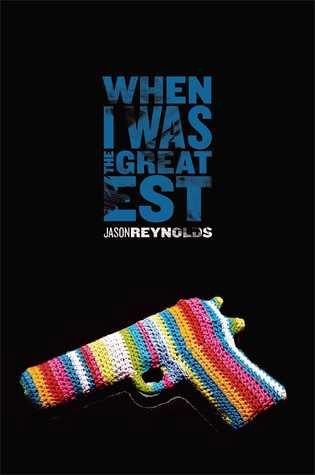

After earning a BA in English from The University of Maryland, College Park, he moved to Brooklyn, New York, where you can often find him walking the four blocks from the train to his apartment talking to himself. Well, not really talking to himself, but just repeating character names and plot lines he thought of on the train, over and over again, because he's afraid he'll forget it all before he gets home. When I Was the Greatest is his debut novel.

You can find his ramblings at IAmJasonReynolds.com.

Jason Reynolds is a wonderful and talented storyteller. He is a fresh new voice and he is boldly and honestly expanding the boundaries of the way that Black Americans are depicted in books and media and opening up a conversation that is long overdue. Jason's characters are rich and complex and human.

DR:So Jason, tell me about your new book.

JR: The new book is titled When I Was the Greatest. It takes place in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It revolves around three teenage boys who are very close friends and who live next door to one another. The narrator is Ali who is sixteen and lives with his mom and his sister. The neighbors are two brothers who are affectionately called "Needles" and "Noodles" by everyone in the neighborhood. "Needles" is a young man who is living his life trying to manage Tourette Syndrome and so a lot of the story takes place around their relationships, around their family lives, around the community and how the community responds to a young person with Tourette Syndrome, how a family responds to a young person with Tourette Syndrome and how friendships sort of change and fall apart or strengthen, for that matter, surrounding a person with Tourette Syndrome.

DR: How did you end up writing about this subject matter?

JR: Funny enough, I worked as a caseworker when I was twenty-six years old.

I had twenty-seven people on my case-load and they ranged from schizophrenics to rapists, child molesters, bi-polar, former drug addicts, convicts, Tourette Syndrome and all of these sort of people who had mental differences and issues that they were trying to work out. My job was to help them to assimilate back into everyday society and get jobs and benefits and things of that nature. So, basically what I was tasked to do was humanize people that had been demonized or pushed to the outskirts of our society for whatever reason.

When I sat down to work on a new project I was really, really fascinated with the fact that in the Black community we really don't deal with mental illness very well. It's one of those things that we kind of sweep under the rug. I noticed even when I had clients on my caseloads, if they had families, those families sort of turned them away or pushed them to the side as though they didn't exist anymore because they were different. I was fascinated by that. I was fascinated to tackle, just a little bit, not all of it because it's a big issue, but to just chip away at a corner of how we respond to mental illness in our community. The funny thing is though, - we don't talk about it but I think that for those of us who know it exists and can acknowledge it exists, I think it's funny how we actually protect the people in our neighborhoods who deal with mental differences. We may not understand it. We may not talk about it. We may hope it never happens to us or talk about in a very sort of cavalier way but...

From my own my experience growing up, we had Lenny. Lenny was a guy who used to walk around the neighborhood talking to himself. He would recite movies line for line, talking to himself. The neighborhood knew him and loved him and protected him, and still does. My mom will call and tell me, "Lenny came over and wanted me to take him to the laundry mat".

Lenny doesn't bother anybody. When neighbors move in we have to warn them, "Hey. Don't be afraid. He's not going to hurt you. He's one of us. He's on this block. He belongs to us. We protect him. You better not say nothin' negative. He's one of us. He's a part of our family".

I wanted to sort of show that from the perspective of teenagers.

DR: I am curious about what your experience is as a Black writer and dealing with the tendency that our culture has to pigeon-hole the kinds of things that Black writers write about and the ways that Black writers represent the Black experience.

JR: Honestly I think it's been a bit shortsighted. For me for instance, I love to write about my folks, my people, specifically in the environment in which I live right now which is Bed-Stuy Brooklyn. I have been in an urban environment my entire life. It's just what I know. And so there are things about the urban environment that do ring true as far as the hustle and bustle of the inner-city environment and people living in close proximity to one another, all these things that are real and true about city living. So there is that. My job is to not lean on those things.

I think that it is easy to take a city like Brooklyn and lean on the negatives and write an entire story based on a stereotype or based on what people see as the norms in these neighborhoods, people who are not on the inside of these neighborhoods. Right? So like you can take an outsider approach and just write a really easy story and make a ton of money. It's easy:

There was a dude

He sells drugs

He killed a man

You know, there is all of this craziness that you can write about that does happen in these neighborhoods but I think it's a bit shortsighted and I think it's a bit one-dimensional and I think its doing a disservice to who we are as a people because the truth is that, though that is happening, there is a whole heap of other stories that are taking place at the same time.

I met a man recently in Connecticut. I was giving a reading. He was a White guy and he was there with his son. He was an older gentleman. He came up to me after the reading and said, "I'm from Philadelphia and I grew up in the Polish community but I used to work in North Philly in the Black neighborhood". He said, "I wanted to let you know that what I realized when I was working in the Black community is that 95% of the people in these neighborhoods live normal lives."

That is exactly what I want to say! We are not "other". We are not these people who are aliens or that are different than anybody else. We go to the grocery store. We go to work. We take care of our babies. We like to sit outside and talk our trash and do whatever we do to commune, but we are normal. We are normal. That's my whole thing. Layers. Complexity. Nuance.

DR: I suspect that that is part of why When I Was the Greatest is experiencing the kind of success that it is because you are connecting with people at the level of humanity so that its not limited to any singular demographic.

JR: That's exactly what it is.

You know its funny, right? What has been done often times in the Black community is, our experience in the projects has become our whole experience when it comes to the representation of us. All of Bed-Stuy has been limited to the Marcy Projects because the Marcy Projects is the most visible thing to the rest of the world due to the celebrity of Jay-Z. Or all of the Black community is limited to Sunday in Church. It's like Sunday in church is now Monday through Saturday as well because of our experience as the cultural part of us that has taken place within the walls of the church, right? But that isn't all we are. That's not who we are. That is a portion of ourselves. That is a small segment. I have a grandmother who was a wild woman but my grandmother wasn't the only person in my family. There were tons of other people in my family.

My father was a hustler and a drug dealer and he drove a car for the mob. But he's a doctor now. My father is covered in tattoos and he's one of the biggest psychiatrists in my hometown. So why is it that I can't tell his whole story?

DR: His whole story.

JR: His whole story.

Why do I only have to pick out portions and talk about when he was a knucklehead. He's not a knucklehead anymore.

When I Was the Greatest

In Bed Stuy, New York, a small misunderstanding can escalate into having a price on your head—even if you're totally clean. This gritty, triumphant debut captures the heart and the hardship of life for an urban teen.

A lot of the stuff that gives my neighborhood a bad name, I don't really mess with. The guns and drugs and all that, not really my thing.

Nah, not his thing. Ali's got enough going on, between school and boxing and helping out at home. His best friend Noodles, though. Now there's a dude looking for trouble - and, somehow, it's always Ali around to pick up the pieces. But, hey, a guy's gotta look out for his boys, right? Besides, it's all small potatoes; it's not like anyone's getting hurt.

And then there's Needles. Needles is Noodles's brother. He's got a syndrome, and gets these ticks and blurts out the wildest, craziest things. It's cool, though: everyone on their street knows he doesn't mean anything by it.

Yeah, it's cool... until Ali and Noodles and Needles find themselves somewhere they never expected to be... somewhere they never should've been-where the people aren't so friendly, and even less forgiving.

DR: Well that's the thing that's kind of interesting to me. Not only are you telling the whole story but you are telling the story that is often not allowed to be told. I think that's more what is significant and important about what you are doing. You are giving yourself the permission to tell the pieces of the story that never get told.

JR: I think for me that's my biggest intention. I want to shine a bit of a light on the quiet pockets of our representation.

I always talk about broken homes and fathers who aren't around. When you think of the Black community the first thing you think of is daddy less families and its crazy because though there are some families who don't have fathers in the home it doesn't mean that there are no fathers in their lives. The divorce rate is the divorce rate across the board. So why is it that in my community it is assumed that these fathers are literally invisible and that they don't exist. It's just not true. It's just a fallacy.

The truth is that there are households without fathers in them but it doesn't mean there are families without fathers in them. There are a lot of families that have fathers that just don't live in the house. I was one of those kids. My dad? We had our problems and we had our issues but at the end of the day, he was a good dude. He did the best he could with what he had. He wasn't this guy who tried to do us dirty. That wasn't the way it went down. Yeah, some things happened that were tough. He had a tough time but he was human. And it's his humanness that I want to portray. I don't want him to be seen as, or fathers in my books to be seen as, monsters because they are not, even the ones that are bad are not monsters.

DR: What is always frustrating for me, Jason, is to listen to the portrayals of Black fathers in the absence of talking about what conditions left them in that way and I just think that there is always a reason why.

JR: There is a reason why. There is always a reason why. As a Black writer my job is to do the work and to try and figure out the best way to give some wholeness to these characters and try and show the reasons why so if you dislike him, you at least can like dislike him with some empathy. You at least can see him as human. You can choose to dislike him based on the information given but it won't be because of this knee-jerk reaction to the fact that he's a Black daddy who's not in the house. I want to try and tear that down and break that down. I'm doing the best I can. And to show mothers who are not angry and who are not bitter. I want to show good solid women who are moms who are doing the best they can with what they have been given. At the same time I want to show their reality being built by their experiences as well. Strength in our community whether it is recognized as strength or not. I want it to always come through.

DR: What are you working on now?

JR: I have a book coming out next year. We just shot the book cover for it. It's called Boy in the Black Suit. It's about a young man who loses his mom to breast cancer, suddenly, and his father spirals and sort of falls off the wagon and back into alcoholism. The young man takes a job at a funeral home and it's at the funeral home that he realizes he has an affinity for funerals. He starts to crash funerals in search of ways to grieve. He seeks solace in people who are seeking solace. Pain is a funny thing in that way.

You kind of watch this kid come undone and then try to put himself back together. Everybody in the story is dealing with some sense of grief from something that has happened in their lives but everyone is sort of dealing and building and figuring out how to place these pieces back where they belong.

DR: I can't wait to read that...

JR: I'm very excited about it and I'm glad that When I Was the Greatest is doing well and I'm really excited for this one because it's going to show Black people in the sacred space of church and in the midst of a sacred ceremony and show how it really goes down. Not just the "song and dance" but it really shows how culturally some of the things that we do that everybody else doesn't do - all the different funerals that we know of.

There are all different kinds of different funerals that take place. When I wrote this book my editor was like "Wow. I didn't even know that there are funerals that are funny". Or as my mother calls some funerals "The Reunerals", where all the old relatives show because they feel guilty about not having been around for so long and they are always the ones that are hollering the most.

Then there are your Small Funerals or your Hat Funerals or your Young Funerals where everybody is dressed in t-shirts and jeans.

T-shirts are a very important thing, especially in an urban environment. These memorials, these urban memorials that we create for our loved ones, should not be seen as hood culture. This is an important part of our culture – the murals on the walls, the t-shirts, the tattoos – it's not just this ghetto shit that people make it seem like. This is a very important thing for a certain generation. I'm really fascinated by these things.

There is this one line in Boy in the Black Suit that sums up the entire thing. The kid is talking to the guy who owns the funeral home. They are in the basement of the guys house and the guy is like, "Do you play chess?" The kid is like, "A little bit." The old man is explaining to him that in New York everybody plays chess. New Yorkers see it as the game of life but he explains that he disagrees with that. "Chess is not the game of life. People say that but it's not. Life can't be that strategic." Then he pulls out a deck of cards and says that "the game of life is I Declare War. I turn a card. You turn a card. Sometimes I win. Sometimes you win, but as long as you still have a cards in your hand the opportunity to win is still there".

That is what the book is about and what my life is about. I win some. I lose some, but as long as I got cards to play the chance of me winning is still there.

DR: Even a card...

JR: Just one card...

DR: Just one card...

JR: The chance of victory still exists.

DR: A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

JR: Honestly I'd love to be remembered for doing my mom and my family proud. I know that's very small in the grand scheme of things.

My mom is from the south and she is a Black woman and she is all the way Black. She loves me and she loves our people and it was important to her that I do something to help, not only our people, but everybody, and do something for the legacy of my folks - all of us.

To do something that people can lean on and say, " This guy was a part of the lineage as Zora and Winston and James, that many, many other writers had an opportunity to come through. I want to be a part of that club. And I don't want to be a part of that club just to be a part of that club. I just want to have a stake and have a brick in that wall to say that, "Like Yo, he was intentional about the work and the art that he was creating to help us to break down some of the fears that people have of us and to show us in a light that we can stand up and be proud of.

I want our kids to be able to hold these books and be proud of who we are, where we are from, how we talk, what we eat, how we move and dance, how we dress. We can be proud of that. It is proprietary. It is special. It is valuable and without it, this world is very, very stale.

Thanks Jason!

Tour Dates

April 10th, Austin, TX

April 25th, Austin, TX

April 26th, Houston, TX

April 28th, Ann Harbor, MI

May 3rd, New York City

May 9th, New York City

For more details, visit http://iamjasonreynolds.com/